MEMORIES OF LIFE AS A TRENCHARD BRAT

By

Rob Knotts

With nearly three

hundred others I joined the Royal Air Force as an Aircraft Apprentice at RAF

Halton on 17th September 1956 as a member of the 84th

Entry. We were some of the many thousands of Trenchard’s Brats that passed

through the hallowed RAF Aircraft Apprentice training grounds of Halton.

Lord Trenchard,

father of the Royal Air Force founded the RAF Apprenticeship scheme which was

launched in October 1919. Selection examinations were held around the country

and in January 1920, the 1st Apprentice Entry comprising 235 recruits began

their three year apprenticeship at RAF Cranwell, whilst permanent accommodation

was being completed at RAF Halton.

The RAF Apprenticeship scheme came

to an end with the graduation of the 155th Entry in 1993. During the 71 years

of Apprentice Training at RAF Halton over 40,000 Aircraft Apprentices

successfully graduated. Among them is a holder of the Victoria Cross, four

recipients of the George Cross, 220 were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross

and 249 won the Distinguished Flying Medal. Approximately, twenty per cent of

Apprentices were commissioned during their service careers, and a

considerable number achieved Air rank.

Whatever their former rank, ex-members of the scheme are very proud

indeed to be known as "Trenchard's

Brats".

Humour was, and

doubtless still is, an essential part of Royal Air Force life. I spent 33 years in the RAF. Throughout my service

career I cannot remember the bad times, only good ones. Humour offset memories

of bad times. The phrase: “If you can’t take a joke you shouldn’t have joined”

was constantly voiced in unpleasant and trying circumstances. Humour was

important for morale. It certainly acted as a bonding force amongst the

apprentices as we adapted to and accommodated the realities of discipline and

service life in our formative years. With gentle humour in mind the following captures

some of my memories of life as a Brat.

How It All Started

When I was born my father

was aged 57. I entered Grammar School at 10 and at 15 gained a sufficient

number of GEC ‘O’ levels, including Mathematics, English and a science subject to

study for ‘A’ levels. However, at the time my father was 72 years old and could

not afford to keep me in sixth form. My uncle had served for 26 years in the

RAF, starting as an Aircraft Apprentice at Halton so we had family experience

of the life. The title page of brochure advertising life as a RAF apprentice is

shown below. I had a great interest in aircraft and opted to join the RAF as a

Trenchard Brat.

Arriving At RAF Halton

I was brought up in

a small village in North Wales. To join the Brats I travelled by train to

London arriving in Euston. From there I transferred to Baker Street to catch

the train to Wendover.

At Wendover we were

met by RAF staff and transported to RAF Halton by bus, similar to the one shown

below.

A tale exists

within Brat circles of would be Brats being met at Wendover by apprentices from

the senior entry who escorted them to Halton, first having collected fares for

the bus journey. It didn’t happen on my journey but it probably had at sometime

in the past!

Medical

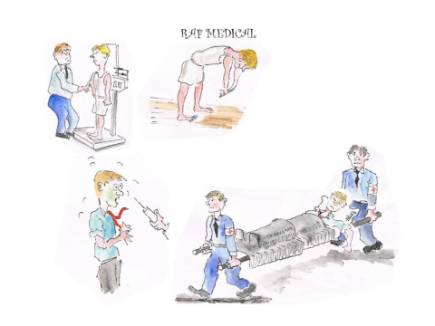

My first major

memory is that of the medical. We were measured, weighed, tested and prodded.

Injections were the order of the day with the occasional future Brat turning

green and then temporarily departing this world when faced with the sight of a

needle.

It Took All Kinds

Brats joined the

RAF between the ages of 15 and 17½. They came from all over the UK and parts of

the Commonwealth. At Halton there were apprentices from Burma, Ceylon, New Zealand,

Rhodesia and Venezuela together with RAF apprentices from many Commonwealth

countries. Some cap badges and shoulder flashes are shown below.

Young men between

the ages of 15 and 17½ joined as Brats for a 3 year course; they had a

commitment to serve for 12 years after reaching the age of 18. We faced our

future in different ways. Many were apprehensive, some quietly confident,

others smug. A few were cynical, occasionally aloof, at first quite a lot

worried bordering at times on being frightened of the future. It took all kinds

to be one of Trenchard’s Brats.

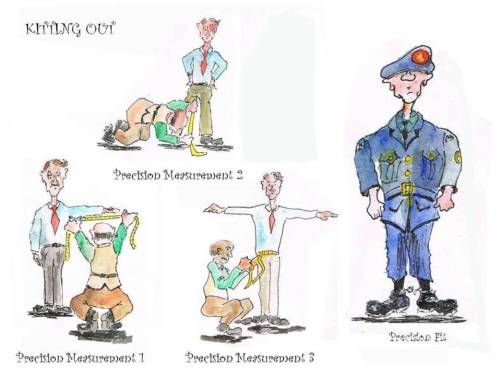

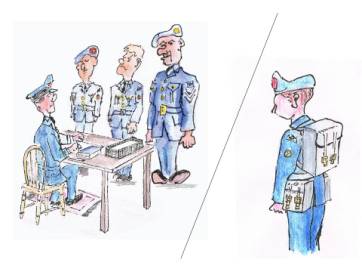

Kitting Out

The next event that

made a major impact was ‘Kitting Out’. In the clothing stores, an area that

reeked of mothballs, we were issued with every article of clothing ‘for the use

of’ deemed necessary to sustain and support us through our life at Halton. The Station tailor made precision measurements

of various parts of us that ultimately led to issue of a uniform that was a

precision fit!

If

The Cap Fits

Berets came in all shapes and sizes

when we were first kitted out. It took some time to get them moulded to our

heads.

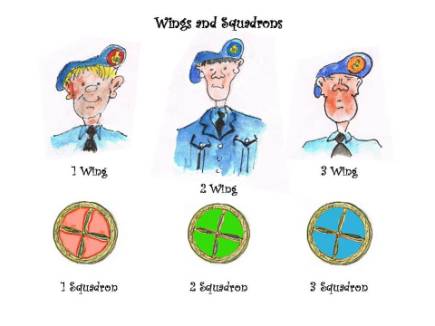

Wings

and Squadrons

There were three

apprentice wings at Halton, each with three squadrons. Each squadron was housed

in two six-roomed, three-storey barrack blocks. Two blocks were allocated per

squadron to accommodate occupants of numbers 1 and 2 flights.

Members of Number 1

Wing wore a red disk behind the cap badge. Number 2 Wing’s disc was blue and

Number 3 Wing’s yellow/orange. SD Caps sported red, blue or yellow/orange hat

bands.

A coloured disk

behind the Apprentice Wheel Badge, worn on the left sleeve, indicated the Squadron:

red was number 1, green number 2 and blue number 3.

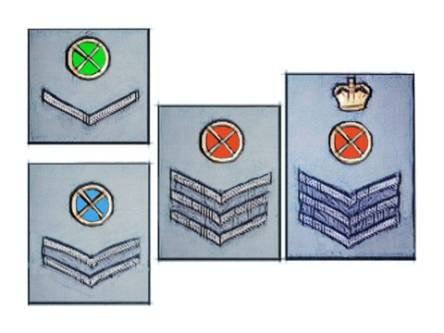

NCO Apprentices

The apprentices had

a NCO rank structure. Basically the Leading Apprentice, known as a Snag, was in

charge of a room, a Corporal in charge of a landing, a Sergeant in charge of a

block and the Flight Sergeant in charge of the Wing. We also had a Warrant

Officer Apprentice in charge of the entry.

Basic Drill

Our first three

weeks in the RAF were spent in the ‘Rook Block’ where the initial efforts were

made to transform us into some form of elementary Aircraft Apprentices. A lot

of the work involved being taught basic drill movements. This involved the

Drill Sergeant armed with a Pace Stick and ‘talking’ to us in a very loud

voice. One instance of being ‘asked’ to be quiet while on parade was deafening.

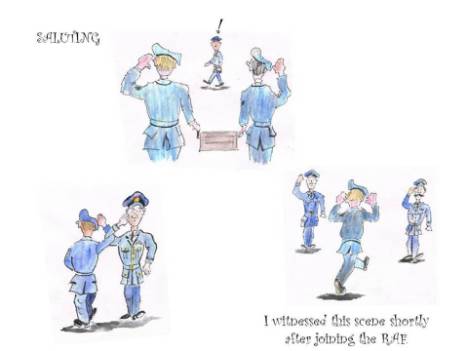

Saluting

One important

element of drill involved the act of saluting an officer; that is recognition

of the Queen’s Commission. This involved bringing the right arm up smartly with

a circular motion to the head, followed by moving the right hand down smartly

to the side by the shortest route.

On one occasion

within a few days of joining the RAF I witnessed one fellow new Brat facing the

presence of two oncoming officers, one to his left and one to his right. You could

almost see the ‘thinks bubbles’ - “What do I do?” Without hesitation both hands

simultaneously gave immaculate salutes, due respect and recognition was given

to both officers, albeit this particular approach did not fully accord with the

RAF’s drill manual.

Haircuts

The standard

haircut was short back and sides. This was in the time that the Tony Curtis and

DA hairstyles were coming into fashion. The modern world looked to longish hair

on men; the RAF maintained the short back and sides as a fashion statement.

We had one shilling

a month (5p in modern currency) extracted from our pay for haircuts. The drill

sergeant made sure that we got value for money. As we became bolder we used to

bribe the hairdresser with one shilling so as not to have short back and

sides. Life was unfair as the drill

sergeant continued to make sure that we got value for our money!

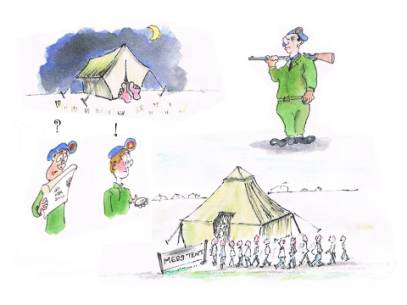

Marching to the Mess

During the first few weeks as apprentices we had to

carry our mug together with knife, fork and spoon (known as Irons) clutched

firmly in the right hand behind the back.

I witnessed the same action many

years later when, as an officer I had to visit a Young Offenders’ prison (at

one time known as Borstal) where one of my airmen was a guest of the HM Prison

Service. I arrived at lunchtime to see a flight of young offenders marching

with mug, with knife, fork and spoon (collectively known in my apprentice time as

Irons) clutched firmly in the right hand behind the back! To think that I had

volunteered to be a Brat with a requirement to carry my mug and irons in such a

manner; these young people were certainly not volunteers. At times life has

some unusual twists.

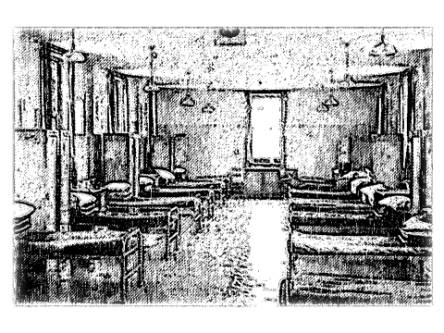

Rooms and Pit Space

We lived 20 to a room, with 10 on

each side. Our domain in that room was limited to our bed space; we called our

bed the pit so we only had pit space to call our own. A locker held some

articles of clothing; the draw in it held our personal effects. We used our

locker top as a table top for writing while we sat on the edge of the bed. We

had a wardrobe in which to hang our uniforms. Bed packs were made every morning

with folded sheets forming layers between folded blankets.

Room Jobs

The Leading Apprentice in charge

of the room prepared and issued a list of room jobs against each occupant. They

included cleaning the ablutions, toilets, stairs and landings, the barrack

block surroundings and the shower to name a few. The junior members of the room

had the most unpleasant jobs. The work was carried out each morning before we

left for Workshops or Schools.

Bull Night and Inspection

Friday night was

bull night in preparation for inspection on Saturday morning. Windows were

cleaned by hanging out of the room concerned; such an action would doubtless

not be tolerated in the current HSE climate. Boots were bulled. Dollops of

orange coloured floor polish were spread on the floor, rubbed in and then bumpered

to produce a mirror-like finish on the brown lino. These activities are just a

handful of the overall work undertaken. Come Saturday morning all that we felt

like doing was falling asleep which would not have gone down well during the

inspection.

Physical Training

Every week we were

subjected to the delights of Physical Training (PT). Dressed in RAF shorts,

coloured a very dark blue, we faced the elements in all weathers under the

direction of Physical Training Instructors (PTIs).

On one winter’s day

when snow was thick on the ground the PTIs assembled members of the Wing on the

square; we were dressed in overalls and boots. They took us for a cross country

run, ending up on the playing fields where we held a massive snowball fight.

Gradually two teams developed, one of about 800 apprentices versus the other of

about 8 PTIs!

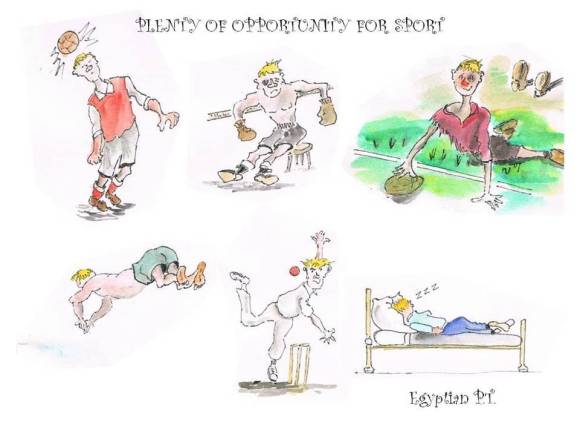

Sports Afternoon

Wednesday afternoon

was allocated to sports. Opportunities for sport were plentiful; soccer and

rugby in the winter, cricket and athletics in the summer. Swimming, boxing,

judo, fencing. cross-country running - opportunities seemed endless. Of course

if nothing took our fancy and if we could get away with it, a very rare

opportunity on a Wednesday afternoon, we could always resort to Egyptian PT.

Trades

Halton Apprentices

were offered training as fitters in the trade of Airframe, Armament, Engine,

Electrical (Air), Electrical (Ground), Instrument (General) and Instrument (Navigation).

Workshops

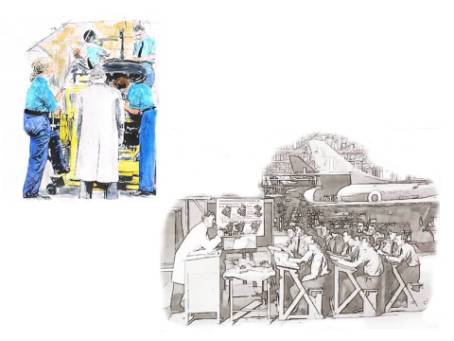

Three days of the

week were devoted to Workshops where we had lectures followed by practical

sessions. Each class held about 20 apprentices. The desks were long wooden

structures as shown below. The practical session shown below portray removal of

a jet engine turbine. The lecture session shown covers one of a Hunter aircraft’s

systems.

School

For one and a half

days each week we attended school in what is now Kermode Hall. We were taught

Mathematics, Engineering Science, Mechanics, Engineering Drawing and General

Studies. Some apprentices gained and Ordinary National Certificate, some

studied for City and Guilds while others attained the RAF Educational Certificate

qualification.

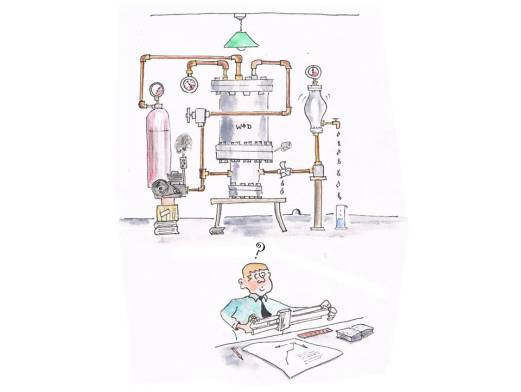

We faced lots of theory and then attempted

to put it into practice in laboratory work where we had to unravel the

mysteries of sophisticated equipment and machinery. Also we faced mastering the

intricacies of the Slide Rule.

Marching to and from Workshops

and School

Members of each

Wing marched to and from workshops and the School every day; down in the

morning, back at lunchtime, down after lunch and back in the evening.

Warrant Officer Bollard

One man who doubtless stands out

in the minds of many apprentices of my era must be Warrant Officer Joe Bollard,

the Station Warrant Officer (SWO). He was the discipline king pin at Halton. He

could spot the need of a haircut, pick out an apprentice not swinging his arms

and recognise an un-pressed uniform from great distances. Each selected erring

apprentice had to report to him during lunchtime. This gave the apprentice

concerned time to march to lunch, suffer indigestion eating it in the few

minutes available before hurrying to keep the SWO’s invitation. Always

immaculately turned out, Mr Bollard made a life-long impression on apprentices

under his charge.

Pay Parades

Pay parades took

place weekly. Number 1 Wing split the parade into two sections. Those with

surname initials A to K were paid on the top floor of the NAAFI. Surnames L to

Z were paid in the gymnasium. The procedure was that a name was called, the

person concerned stepped forward stating “Sir” adding the last three digits of

his service number. He saluted and received his pay.

My surname meant

that I was paid at the end of A to K batch; in fact I was the very last to be

paid. I always feared that by the time payment got to me the paying officer

would have run out of money.

Charges and Jankers

Punishment was administered if an apprentice committed a minor breach of

discipline. The process started with someone being placed on a charge. The

alleged offence was entered on a Charge Report (RAF Form No. 252).

An officer heard the charge. The accused was marched into the hearing

without wearing a hat; this could be used as a weapon. He was accompanied by an

escort, who wore a hat. Witnesses were summoned one by one to give evidence. Also

present was the Orderly Room SNCO. Before the officer considered if there was a

case to answer the accused was given an opportunity to make a statement.

If the accused was found guilty the punishment handed out might be a few

days of restrictions, that is ‘Jankers’, a term for an official punishment. The unfortunate on ‘Jankers’ had to wear full

webbing kit and report to the guardroom at various times during the day for

inspection by the Orderly Officer. Restrictions also included a couple of hours

of fatigues, normally cleaning duties, every evening.

Lewis the Goat

The history behind having goats as

mascots at RAF Halton dates back to World War Two when the Royal Welch

Fusiliers left their goat Lewis with the RAF Apprentices when they were sent to

the front. The RAF Apprentices adopted the goat and the history continued until

1993 when the last RAF Apprentice entry graduated.

During the long periods of standing

still while on parade my mind wandered to many things. One thought was what if

Lewis the Goat broke loose, what would happen?

NAAFI Break

We had a break mid

morning and mid afternoon where the NAAFI wagon offered refreshments, including

the famous (in Brat circles) Nelson. It was a square of very solid bread and

butter pudding topped with a layer of pink icing. It was the nearest thing in

the 1950s to a black hole – it was so dense. Inevitably there was always a rush

to get to the wagon.

The Astra

In the days when

Television sets were few and far between on camp the Astra cinema, located in a white 1930s

building, offered film entertainment and an escape from the daily Brat routine.

Always evident was the roar and shouts

of “Good Old Fred” as Fred Quimby’s name came up on the credits for ‘Tom and Jerry’

cartoons.

Another recurring incident was the

response to a notice being flashed on the screen during a film show. Inevitably

it asked the Orderly Corporal to report to the Booking Office. This was always

met with a loud response; “He’s Gone to the Pictures!”

The Court School of Dancing

Quite a few

apprentices in our era were ‘graduates’ of the Courts School of Dancing in

Aylesbury just opposite the Queen’s Head pub. The motive was straight forward.

Being healthy young men we had a natural interest in meeting young ladies. One

sure way of doing so was to learn to dance. So we enrolled at the dancing

school albeit initial efforts were clouded by having parade ground feet which

left many a girl’s toes bruised. However, with patience on the part of the

dance instructors we eventually became passable dancing partners.

At the dancing

school romances bloomed and often faded. However, some flourished. One of our

entry members married a girl he met at the Court School of Dancing. He retired

as a Wing Commander and lives with his wife in southern Germany.

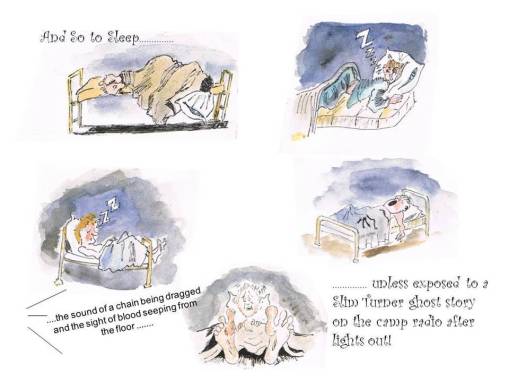

And So to Sleep

Apprentices lived

20 to a room in large three-storey, six-roomed barrack blocks built on the edge

of the parade square. It was a daunting experience living in such surrounds.

The room housed members of each entry; nine entries were resident at Halton.

The senior entry members slept at the end of the room, the junior entry members

near the door. As entries graduated members moved up the room to make way for

incoming juniors. Lights out were at 10.30 pm at which time it didn’t take long

before sleep embraced a room’s occupants, unless Slim Turner exposed us to a

ghost story on the camp radio.

Slim Turner was a SIB

Corporal in the RAF Police. He lived on base. After duty he operated the camp

radio system that was piped through to a speaker in very barrack room. About

once a term after lights out he would read a ghost story. Imagine the scene.

Each barrack room is shrouded in darkness. Twenty apprentices in each room

could not fail to hear the story. Inevitably it related to some ghostly

occurrence purported to have occurred somewhere on camp. One I remember

involved a ghostly occurrence in a barrack block’s ‘drying room’ where under

certain conditions blood could be seen seeping up through the floor while

accompanied by the noise of chains being dragged along the floor. After the

story even the most macho apprentice in a room would not take an after lights

out trot to the bog which was near to the drying room.

Musical Apprentices

Quite a few

apprentices became accomplished musicians. Each Wing had a pipe band and a core

of trumpeters. The Apprentices also fielded a military band.

Daily we marched

from the Wings to workshops or schools and back again; in the morning, back for

lunch and out again led by pipe bands and drums to return in the evening. On

parade days we also marched to the military band.

Summer Camp

In July 1958 we

spent two weeks at RAF Woodvale, on Summer Camp. We marched to the railway

station at Tring from where we transported to Woodvale halt by train. From

there we marched to RAF Woodvale, a coastal airfield in sand dune country,

about 6 miles South of Southport, on the Lancashire coast. Living in 6-man

tents for 2 weeks, we spent the days engaged in various pursuits such as route

marches, map reading, sport, firing rifles and bren guns, military exercises by

day and night and flying around the local area in Ansons. Off duty we chased

the girls in Southport. Liverpool was also nearby but incidents of polio there placed

it off limits. Throughout the day we wore overalls, after duty uniform.

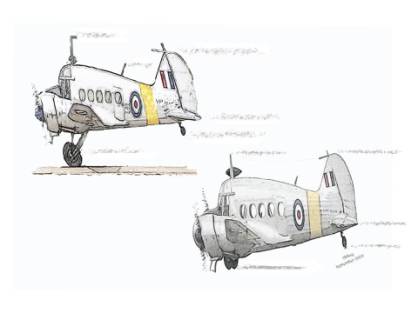

Flying

In the 1950s relatively

few people travelled by air. Flying offered a very new experience to most of

us. My first opportunity came during our Summer Camp at RAF Woodvale when I,

and many others, took to the air for the very first time in a Royal Air Force

Avro Anson, registration VP 509. The Anson is shown struggling to get into the

air and then chugging its way through the sky.

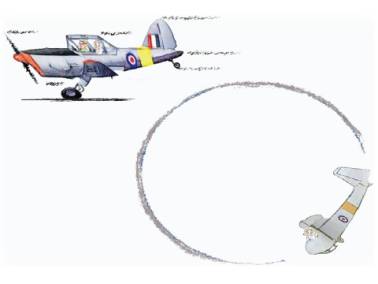

There were also

opportunities to fly at Halton, either by gliding or with flights in DH

Chipmunks based at the airfield.

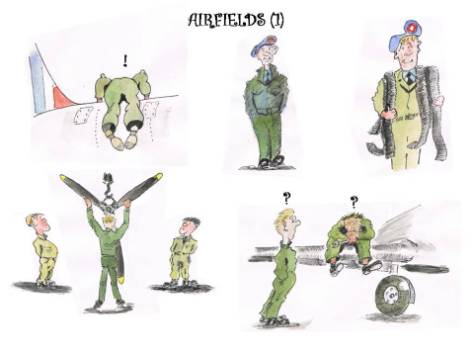

Airfields

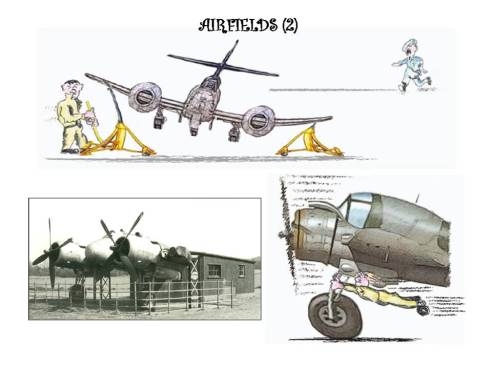

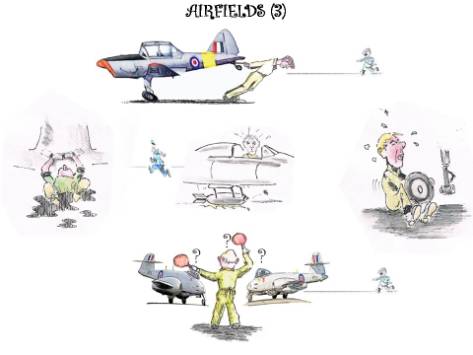

The final part of

our three year training course covered the ‘Airfields’ phase. The airfields

were located near Halton village.

The verb “To Trog”

probably originated at Halton. It describes the act of marching without

swinging arms, really more of a slouch. On reaching this final phase of our

training we were issued with the coveted ‘Trog Mac’, a coat made out of some

black plastic type material that had its own very distinctive smell. It was a memorable day when we were issued

with them. We were the senior entry and the ‘Trog Mac’ was worn with pride to

impress junior entries. The fashion was to have one far too long so that it

almost reached the ground. We marched to and from the airfield without swinging

our arms, that is we trogged in our ‘Trog Macs’.

In the airfield

phase we applied what we had learnt to real live aircraft. The machines faced

removal of propellers and engines; they were inspected, armed, repaired, towed and

pondered over. We moved aircraft, we marshalled them. At long last we were

within the realms of the real live world of aircraft.

Aircraft on the

airfield included Mosquitoes, Meteors, Swifts, a Valetta, a Brigand and a

Lincoln. In the hangars there were Canberras, Hunters and a Javelin.

The riggers had the

opportunity to try their hand at jacking aircraft. For the engine fitters, the

Sooties, there was a cockpit classroom. This was a Beaufighter aircraft nose

fitted to a shed that offered hands on engine testing opportunities on Bristol

Hercules engines. For each run a ‘volunteer’ had to prime the engine by pumping

a ‘Kigas’ fuel pump located in the port undercarriage bay beneath the engine.

The ‘volunteer’ was encompassed in engine smoke as the engine burst into life

and he was then exposed to the powerful airstream. When the engine was running

he had to gently withdraw himself from under the aircraft with a propeller spinning

within a short distance of his head.

During the airfield

phase we had a chance to hone our skills. Armourers removed and fitted ‘bang

seats’, loaded weapons and tested guns. Electricians chased wiggly amps.

Instrument bashers fitted and tested a multitude of sensors and indicators. Riggers patched holes, fixed flying controls and sorted out

hydraulic systems. Sooties changed plugs, removed engines, replenished oil

systems and generally got dirty. The phase showed us that some tasks

were dirty, some mentally challenging, some physically demanding and that some

could lead to frightening situations. In certain cases we made mistakes, and

hopefully learnt from them. A SNCO was always on hand to ensure our safety.

DH Comet

During our airfield

phase DH Comet G-ALYT was delivered to Halton as a training aircraft for RAF

apprentices. Flown in by the famous WW2 ex-RAF night fighter pilot Group

Captain Cunningham it was doubtless a hazardous operation to land the Comet on

a short, grass airfield.

The Future We Faced

In July 1959 we

completed our apprentice training and departed Halton to work in the big wide RAF

world. In those days there were RAF bases all over the World including Aden,

Borneo, Cyprus, Gan, Germany, Gibraltar, Libya, Malaya, Malta and Singapore.

Aircraft were many and varied: Argosies, Beverleys, Britannias, Canberras, Hunters,

Meteors, Swifts, Shackletons, Vampires, Varsities, Valiants, Victors and

Vulcans, to name a handful. As time progressed other aircraft came on the scene

such as Buccaneers, C130s, Jaguars, Phantoms, Tornadoes and VC10s and

helicopters such as the Sea King and Puma.

Some aircraft types

worked on by members of our entry through their service careers are shown

below.

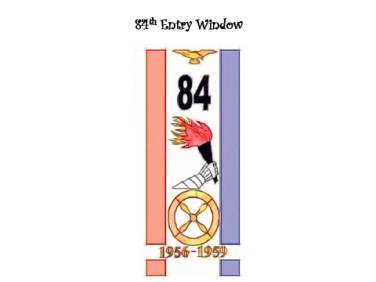

84th Entry Badge

Each entry designed

its own entry badge. Our entry’s badge is shown below.

84th Entry Window

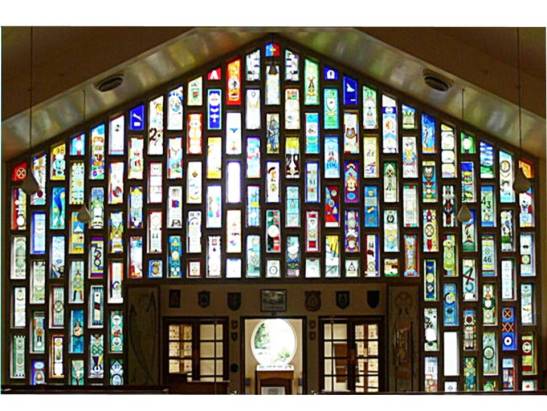

In 1997 Rev Richard

Lee, the RAF C of E Padre at St Georges Church, Halton at the time, suggested

that the RAF Halton Aircraft Apprentices Association (RAF HAAA) encouraged its

members to install stained glass windows in the church to commemorate their

time as Brats. The RAF HAAA bought into the idea and soon windows, depicting entry

numbers, wing colours, entry badges, famous (and infamous!), entry activities

and a host of other events were appearing in glorious coloured glass: each

telling something of an entry’s time at Halton. Our entry’s window is shown below.

The stained glass

window in St George’s church is shown below. Any attempt to paint the window

would not do it justice; a cartoon would lower its dignity. Consequently it’s

shown as is. It really is a magnificent tribute to Trenchard’s Brats.

Website http://www.oldhaltonians.co.uk/pages/rememb/windows/windows.htm

carries a picture of each of the windows installed in St George’s church with

many accompanied by an associated description.

Reunions

Since our days as

Brats many of us have attended a number of RAF Halton Aircraft Apprentice

Association reunions. Group Captain Christine Elliot was appointed Station

Commander at Royal Air Force Halton only a few days before the triennial

reunion held on 25 September 2010. She was the first woman to be appointed

Officer Commanding at RAF Halton.

Facing hundreds of

aged juveniles in the form of ‘Trenchard’s Brats’ must have been a daunting

experience. However, the event was met with extreme grace, a friendly smile and

good humour.

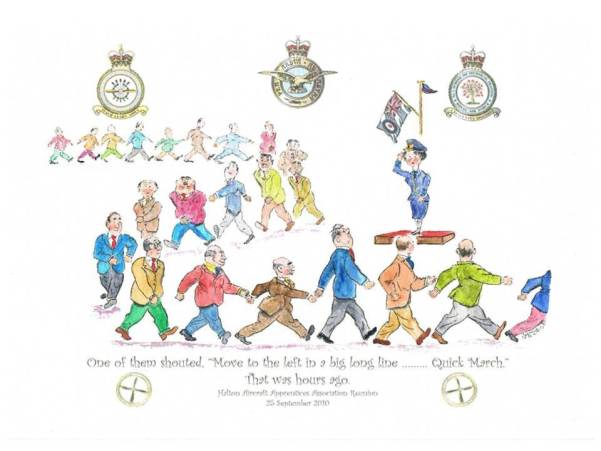

I decided to

capture the reunion march past in cartoon form. I sent the original to Group

Captain Elliot as a memento. It

portrays, with gentle humour, a lengthy march past with some ex-Brats out of

step but still giving their best in respect of the Station Commander, as a

tribute to Halton and to honour those no longer on parade.

The

Last Man Left in the Air Force

Someone recently

sent me the following, written by ex RAF Master Signaller P. I. Fisher (also an

ex Brat) under the nom de plume “Peter Wyton”. I find it extremely amusing.

|

|